The 2020 Mike Stewart Pipeline Invitational had eight women competing. Six of them had to compete in Round 1 with 58 other men.

There were 16 heats that lasted 20 minutes, with four people per heat. The top two contestants would advance to Round 2, which was held the same day as Round 1.

Two women and 30 men advanced from Round 1 into Round 2, where they competed against each other in four-person heats.

The top two competitors from each heat then advanced to the second day of competition, making a total of 16 people to advance to Round 3.

Only one of those 16 athletes was a woman.

Two days later, a new swell filled in, and Round 3 was held with the 16 people that advanced from Round 2 and also competitors that were seeded into the later rounds.

Being seeded means that you do not have to compete in the earlier Rounds 1 and 2 because you ranked highly on the contest or tour last year.

Instead, the competitor is automatically “seeded” – or placed – into an advanced round with higher-ranked competitors.

Two women were seeded this year into Round 3 – myself and Ayaka Suzuki – who had also competed with the men on the final day of the competition in the year prior.

Miya Inoue was the only woman that advanced to Round 3. The three remaining women were placed into eight, four-person heats.

Ayaka and Miya were placed into the same heat with two other men, while I was competing against three men in my heat.

I came in third place out of the four people.

Ayaka and Miya both advanced in their heat, defeating the two men they were competing against.

Ayaka and Miya then advanced on to Round 4 along with 41 other men who also advanced.

These competitors would then compete against 16 more seeded men in eight heats, with four people in each heat.

Both women were placed in the same heat – Heat 5- and only one, Miya, advanced to Round 5, otherwise known as the quarterfinals.

The quarterfinals consisted of 16 contestants.

Only two of those contestants, one woman (Miya Inoue) and one man (Keahi Parker), had competed on the first day in Round 1 and two and had advanced all the way without being seeded.

The conditions of the waves had changed dramatically as the day progressed, and the waves were significantly better later in the day.

Miya competed in the quarterfinals against three men and got a fourth place, which did not let her advance into the next round.

The Women’s Results

The final ranking of the women competitors that entered the 2020 Mike Stewart Pipeline Invitational are as follows:

13. Miya Inoue (JAP)

25. Ayaka Suzuki (JAP)

33. Traci Effinger (HAW)

65. Valentina Diaz (CHI)

65. Aoi Koike (JAP)

81. Momo Aida (JAP)

81. Kanesa Duncan Seraphin (HA)

81. Mayumi Kondo (JAP)

However, after the event was finished, there was an award ceremony at the podium in which tiki trophies were passed out to the women based on the highest scores that they received in their individual heats, not their ranking.

In other words, the women did not compete against each other directly but were judged on how well they did against the men in their heat.

This system of ranking women creates ongoing oppression, which causes controversy for multiple reasons.

Ranking women against women who surfed against men is unequitable because the conditions are different in each of the women’s heats.

Conditions vary greatly between heats, and even within heats.

Some heats could have much better waves while other heats could be during a lull or worse conditions.

So, to take a woman’s score from one heat and compare it to another woman’s score during a different part of the day, or a different day completely, is inequitable and inaccurate ranking.

However, if it were all women competing against each other during these poor, or great conditions, it could then be considered equitable to advance the top 2 or rank them based on their performance.

In addition, when comparing women’s scores who were placed in different rounds, the women in the higher rounds could be up against male competitors who have more experience and are harder to beat.

Those women that were seeded also had another man seeded with them, who did very well in the competition last year, and are highly advanced competitors.

This is a different level of a competitor than a Round 1 competitor, who is not seeded and might never have surfed Pipeline before.

The number of good waves that the highly advanced male competitor catches will affect the number of available waves left in the heat for the woman.

So the more advanced the male competitor, the more difficult the heat is.

And most importantly, the skill level of a woman contender in any conditions at Pipeline cannot be ranked against another woman unless they are directly competing against a woman in every round of the competition.

Entering into an event at Pipeline itself can be extremely nerve-racking.

Then, adding the dynamic of being a woman competing against men can cause additional anxiety and nervousness that might affect an athlete’s performance.

If the women had the opportunity to compete against other women, it could relieve some of this anxiety, freeing up mental barriers that can affect bodyboarding abilities under pressure.

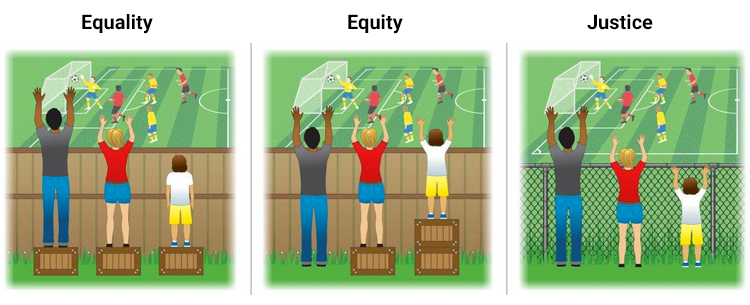

Equality is not Equity

The bodyboarding community needs to understand is that equality is not equity and that putting women on an equal playing field is not advocating for women’s bodyboarding.

I will give an example to help demonstrate this difference.

Picture that there are three kids that want to see a baseball game but that there is a fence, made of solid wood, that keeps them from seeing the game.

One kid is 5’5,” and he can easily see over the fence without any accommodations.

One kid is 5” tall and he can’t see over the fence, and the other kid is 4’8,” and he can’t see either.

Equality is the assumption that everyone benefits from the same supports. This is equal treatment.

So, giving every kid a 5” block to stand on, including the one who can already see.

The kid who is 5′ tall can now see, however, the shortest kid, still can’t see over the fence, even with the block.

Equity is when everyone gets the supports they need – this is the concept of “affirmative action,” thus producing equity.

So, in this case, the tallest kid doesn’t get a box because he doesn’t need one to see.

The 5′ tall kid gets one block so he can see, and the 4’8” kid gets two blocks so he can see.

Justice is when all three can see the game without supports or accommodations because the cause of the inequity was addressed.

The systematic barrier has been removed.

A Constructive Suggestion

So in our example’s case, the wood fence was torn down, and a see-through chain link fence was put up.

This example relates to bodyboarding in many ways.

Trying to say that women, juniors, and drop-knee riders have an equal playing ground and then putting them into a prone men’s competition is not equity and will not help the sport thrive.

Each unique division should have its own heats to compete against each other so that justice is achieved, and those barriers to competition are removed.

Creating those divisions which will include women versus women heats, drop-knee versus drop-knee, etc., will be giving these unique riders the support they need to succeed – equity.

Hawaii and Resolution 20-12

I am currently on the committee of Resolution 20-12 in the Hawaiian State Legislature that addresses gender equity in surfing competitions.

Gender equity is part of the Olympic process for surfing, and as such, Hawaii should support this resolution for all water sports competitions within the state, including bodyboarding.

The only other athletic competition pitting a man against a woman was Billie Jean King versus Bobby Riggs (Battle of the Sexes, 1973).

If bodyboarding or any other competitive sport is to move forward and gain publicity and recognition in the public’s eye, there needs to be more equity in these competitions.

The 2019 Women’s Pipeline Pro for bodyboarding was the only all-female competition that men were not allowed to enter in the past two years at Pipeline.

The mental state of a competitor is different when a woman is competing against other women versus men, despite how good these competitors might be.

We, as women bodyboarders, don’t believe it is equitable that a female versus female competition has been taken away from us and replaced with an invitation to compete against men.

In the past two years of the Mike Stewart Pipeline Invitational, the women were given the title of first, second, and third place according to their points that they earned in their heat in which they competed and lost to the men.

These results are not accurate representations of the actual placement that the women did in the competition, but they make the women feel better about paying a $285 entrance fee by giving them a trinket to hang on their wall, a slap on the back, and being told they did a “good job.”

Women don’t want a trinket or a slap on the back.

Women want an equitable competition with their own division with similar opportunities for prizing and ranking.

Then, true social justice will be served, and women will be recognized for their efforts equitably.

Words by Traci Effinger | Professional Hawaiian Bodyboarder

Recent Comments