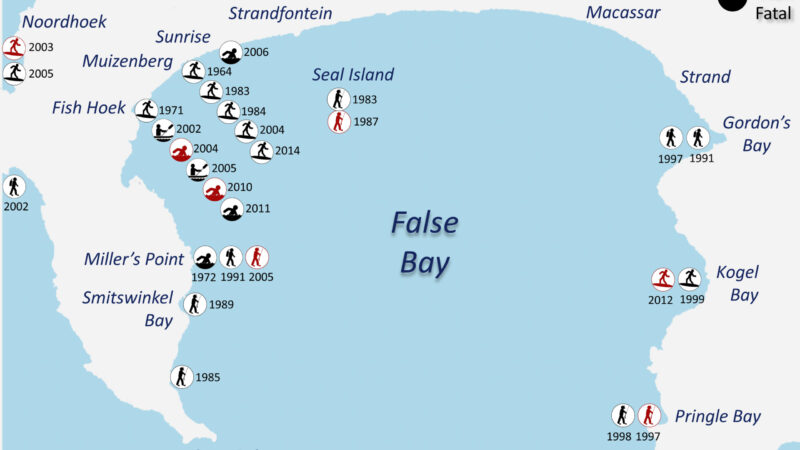

Used to be, the biggest dilemma Cape Cod surfers faced was how to keep their bounty of barreling beachbreaks secret. Comparatively benign to the problem they’re dealing with now. Last September, Massachusetts was dealt its first shark fatality in 83 years when a 26-year-old college student, Arthur Medici, was killed by a great white while bodyboarding off Newcomb Hollow Beach in Wellfleet. Between that tragic day and a recent surge in great white shark sightings off Cape Cod, vigilance if not dread has overshadowed the hurricane-season stoke that typically circulates through the surf community here.

A lone lurker at Nauset Beach. Photo: Trevor Murphy

“The Hurricane Joaquin swell, October 2015, was the last time I shot in warm water here,” longtime local surf photographer Luke Simpson admits. “I decided it was still worth being in the water to surf, but water photography wasn’t worth the risk during the time of year when we see the most shark activity. Thankfully, the overwhelming majority of good surf here happens in water temperatures that white sharks don’t seem to enjoy [winter]. But there are people who don’t surf here anymore, people who haven’t changed their surf habits at all, and everything in between. It seems like a lot more people are riding SUPs, which limit exposure to the water, and some are even using electronic deterrents like Shark Shields.”

View: Cape Cod Regional Forecast

“For a lot of us, though, attitudes towards surfing here had changed well prior to last year’s tragic events,” Simpson continues. “Seeing a 600-pound seal on the losing end of a predation event at your favorite sandbar is horrifying, and at this point, that’s something that almost all our local surfers have witnessed. It might have taken a human fatality to get the attention of the national media, but with those types of Discovery Channel food chain scenes taking place in real life, the local surf community has been paying attention for several years.”

“While sharks have always been a part of the waters near Cape Cod’s marine environment, researchers have seen their numbers grow over the years,” CNN reported. “White sharks were designated as a protected species in federal waters beginning in 1997, and Massachusetts designated them as a protected species in state waters beginning in 2005. Combine the protected status of sharks along with the growing seal population and it was only a matter of time before their numbers grew.”

An ominous carcass at Wellfleet. Photo: Trevor Murphy

This summer, over 30 great whites were reported in a single week in Atlantic waters all along the Outer and Lower Cape, as well as in Cape Cod Bay down to Wellfleet Harbor. Researchers tagged 12 near Cape Cod Bay alone, according to data from the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy’s App, Sharktivity, which was developed in collaboration with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, the Cape Cod National Seashore, and officials from Cape Cod and South Shore towns to raise awareness of these creatures’ presence off the coast. And as we move closer to the climatological peak of hurricane season, with an uptick in surfer traffic inevitable, first responders aren’t messing around.

“People are no longer incredulous to the potential danger,” Anthony Pike, Orleans fire chief, told Fox News. “We’re seeing a cultural change across Cape Cod to educate the public, to stay close to shore and swim responsibly. This problem has intensified over the last decade. We’re really taking an aggressive posture this year.”

Orleans carries the grim distinction of becoming one of the first towns in the United States to install severe bleeding kits beachside (containing tourniquet, eye protection, gloves and trauma dressings), emergency call boxes in more remote places that have limited or no cell service like Nauset Light Beach, as well as bold if not disturbing signage, enhanced safety protocols and new communication towers.

Otherwise perfect conditions in Orleans. Photo: Trevor Murphy

“There were a lot of positive changes that came about after last summer,” Simpson continues. “Many of us have taken a class called ‘Stop the Bleed’ where you learn how to control life-threatening bleeding. One of the things they taught us was that a surf leash isn’t a real effective tourniquet because you can’t get it tight enough. Now all the beaches have bleeding control kits available, even when the lifeguards are off duty. And the lifeguards have purchased new equipment and received additional training from the state scientists who are trying to understand more about local shark behavior.”

Then there’s the fragility of property values to think about, and the seasonal tourist industry demanding business owners make their money in three months. “There have always been sharks on the Cape, but in the last couple of years the situation has exponentially intensified into a true problem,” says Robbie Goodwin, Massachusetts’ most promising young surfer. “It’s not only a bad thing for the local surf community. It’s bad for the summer tourism, the local businesses, and the whole outlook of the Cape itself.”

Research and reconnaissance in Cape Cod. Photo: Trevor Murphy

“The shark issue affecting Cape Cod really hits home on a couple of different levels,” local surf photographer Trevor Murphy agrees. “Obviously, swimming around with my camera and surfing with these giant apex predators has its drawbacks: fear, death and just the whole mindset of not being in control. More important than the hampered leisure activities, though, is the fact that Cape Cod is a major tourist destination. A horror movie playing out live at your summer beach party doesn’t go over too well with the average tourist. The closed beaches and the vacations cut short are starting to take their toll on the local economy. Only time will tell for how long.”

“This is a new issue for us,” Simpson finishes. “Fifteen years ago, sharks were the last thing a surfer here would concern themselves with. Each season, though, there’s an increase in shark activity. At some point it will level off, and that will be our new normal. Hopefully by then, the scientists will better understand the behavior of the local shark population. We will all have to assess the risk, and make decisions based on what we’re personally comfortable with.”

Recent Comments